When Margaret Nettlefold planned the garden at Winterbourne, daughter Valerie revealed that her mother ‘lived with gardening books for a year or so’. Here, the influence of Gertrude Jekyll is inescapable. Winterbourne is filled with Jekyllian detail inspired by her 1899 classic Wood and Garden. Each month, we follow in Margaret’s footsteps to see how the garden compares now and then…

“And June is the time of Roses. I have great delight in the best of old garden Roses; the Provence (Cabbage Rose), sweetest of all sweets, and the Moss Rose, its crested variety; the early Damask, and its red and white striped kind; the old, nearly single, Reine Blanche. I do not know the origin of this charming Rose…” Gertrude Jekyll, Wood and Garden, 1899

The house and garden were bequeathed to the University of Birmingham in 1944 and Margaret’s Edwardian Walled Garden was quickly converted into a space for educating students. In the 1960s the Walled Garden was given another dramatic makeover when row upon row of natural order beds were replaced instead with hundreds of roses. The National Collection of the History of the Rose might have been more colourful but it was certainly no less educational.

Professor J.G. Hawkes wrote this guide in 1995 to accompany the National Collection

Designed by Professor J.G. Hawkes, alongside garden staff, the collection was intended to illustrate the ancient origins of modern hybridised roses in a series of chronologically arranged borders. Hawkes was Mason Professor of Botany, later Chairman of the Friends of Winterbourne, and a world-renowned expert in the evolution of domesticated plants.

Professor J.G. Hawkes with horticultural student Elizabeth Connelley in the Herb Circle

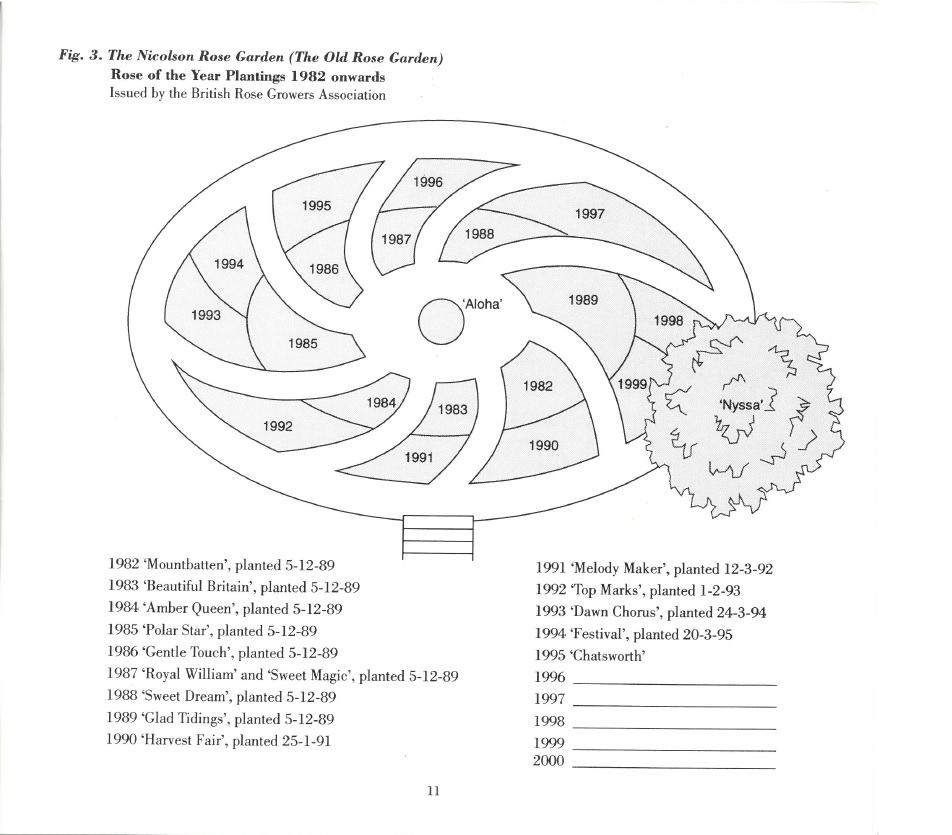

Used to teach both under and post-graduate courses, students of botany could begin at one corner of the Walled Garden, in the cradle of the ancient civilizations of Egypt, Minoan Crete, Persia and China, and end in the Sunken Garden with the most recent winners of the ‘Rose of the Year’ competition; a hotly contested accolade awarded to the best new varieties by the British Association of Rose Breeders following extensive trials.

“After many years of fruitless effort I have to allow that I am beaten in the attempt to grow the Grand Roses in the Hybrid Perpetual class. They plainly show their dislike to our dry hill, even when their beds are as well enriched as I can contrive or afford to make them.” Gertrude Jekyll, Wood and Garden, 1899

The development of the modern rose is a highly complex story which can be made less so by considering three broadly defined groups; species from Europe and Western Asia, species from the Far East, and hybrids occurring between the two. This hybridisation began when the China roses were first brought to Europe in 1792 and from here all the modern European hybrids were eventually created.

Plan for the Sunken Garden displaying the ‘Rose of the Year’ collection, 1995

Of the European and West Asian roses, four species are perhaps the most significant, including the red rose of Lancaster (grown by Persians as early as the 12th Century BC), musk rose, Phoenician rose (found in ancient Egyptian tombs) and dog rose. From these four species many well-known hybrids have resulted, notably the damask rose, white rose of York, and the cabbage rose.

The Walled Garden in the 1990s, photograph by Anthony Spettigue

Far Eastern roses were probably derived from two species; the China Rose and the tea rose. These had been cultivated in China for centuries when Europeans first imported them in the late 18th Century. The tea rose has a scent similar to tea blossom and flowers perpetually (a desirable quality driving much modern breeding). Students of the National Collection were able to observe tea roses flowering into September long after the European and West Asian roses had finished.

“But the Tea Roses are more accommodating, and do fairly well, though, of course, not so well as in a stiffer soil. If I were planting again I should grow a still larger proportion of the kinds I have now found to do best. Far beyond is Madame Lambard, good alike early and late, and beautiful at all times.” Gertrude Jekyll, Wood and Garden, 1899

Breeders hybridising the European and West Asian roses with Far Eastern species sought to combine the best of both divisions. Hybrid perpetuals first appeared in 1825, bred at the Empress Josephine’s Malmaison near Paris, followed in 1837 by the first garden-worthy yellow rose (blues remain elusive). By far the most popular of this group are the hybrid teas (a cross between hybrid perpetuals and teas) containing the long-flowering qualities of the China roses in a wide range of colours.

The ‘new look’ Walled Garden in 2012, photograph by Phil Smith

Sadly, in the early 2000s the collection began to show signs of rose sickness, a little understood disease believed to result from a build-up of certain pathogens in the soil, where roses have been grown for long periods of time. The Garden Team removed those roses that appeared most susceptible and left those that were showing some signs of resistance.

The Walled Garden today, photograph by Mark Barrett

The remaining roses were then inter-planted with summer flowering perennials such as foxgloves, peonies, and cat-mint, whilst the borders were altered (and made larger) to further enhance the ‘new look’ Walled Garden. Today, the National Collection has gone, but its legacy lives on in a garden of many meanings, and visitors can still enjoy the surviving roses when they bloom as part of a new floriferous planting scheme.

11°C

11°C

Totik Sri Mariani

The house and garden are very beautiful. I hope I could visit it.

Daniel Cartwright

Thanks very much Totik!